Humans are complex creatures yearning for simple answers. Just as we search for a panacea—that single drug or supplement or food ingredient that will heal all ills (and maybe dodge the effects of aging while we’re at it)—we seek panacea’s disease corollary: that single gene or molecule or biological trigger at the root of all illnesses.

Many believe they have found it: leaky gut syndrome.

What is leaky gut syndrome?

Generally, the thin epithelial lining of the intestine takes up large molecules across cells (transcellular) and very small molecules, like water and electrolytes, via the spaces between those cells (paracellular), also known as tight junctions. Abnormal paracellular function allows larger molecules across those tight junctions: the leakiness that is leaky gut.

Generally, the thin epithelial lining of the intestine takes up large molecules across cells (transcellular) and very small molecules, like water and electrolytes, via the spaces between those cells (paracellular), also known as tight junctions. Abnormal paracellular function allows larger molecules across those tight junctions: the leakiness that is leaky gut.

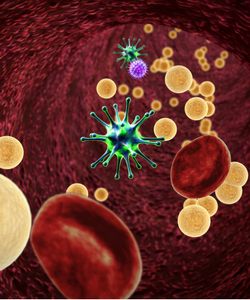

Proponents of the leaky gut syndrome theory hold that this leakiness allows undesirable particles—bacteria, allergens, toxins, food molecules—to enter the bloodstream and or lymphatic system, leading to a cascade of inflammation, systemic immune response and the wreaking all sorts of health havoc: from gastrointestinal disorders and autoimmune conditions to migraines, metabolic disorders and autism.

Not enough human testing

"It’s a very neat idea," says Eamonn Quigley, MD, head of gastroenterology and hepatology at Houston Methodist Hospital. But that neat idea extrapolates directly from animal models and does so without corresponding evidence that undesirable molecules "leaked" through, he says. Quigley, who is also professor of medicine and internationally recognized researcher in digestive disorders, explains that while intestinal permeability, and specifically bacterial translocation, is well known to occur in animal models, satisfactory testing for the same mechanism in humans is lacking.

"It’s a very neat idea," says Eamonn Quigley, MD, head of gastroenterology and hepatology at Houston Methodist Hospital. But that neat idea extrapolates directly from animal models and does so without corresponding evidence that undesirable molecules "leaked" through, he says. Quigley, who is also professor of medicine and internationally recognized researcher in digestive disorders, explains that while intestinal permeability, and specifically bacterial translocation, is well known to occur in animal models, satisfactory testing for the same mechanism in humans is lacking.

Without live tissue analysis, detection of abnormal intestinal permeability in humans proves technically challenging, in part because the intestinal barrier is not always a barrier. In fact, Quigley says, it’s not that simple. Information moves back and forth across the epithelial layer: "It is a two-way street, absolutely."

Although increased permeability is associated with both severe stress and inflammation, Quigley notes the chicken-and-egg question of primacy: did the permeability cause the disease state, or is it the other way around? "People kind of grabbed onto this theory and applied it to a whole host of illnesses, the most part for which there’s no data," he says.

An alternative perspective

"This is not something that we in integrated medicine or in nutrition just made up," says Liz Lipski, certified nutrition specialist and academic director of nutrition and integrative health, Maryland University of Integrative Health. "It’s real, and it exists. And it contributes to a lot of health issues, including autoimmune disease and so many other things." Lipski, who published her book Leaky Gut Syndrome in 1998, believes the disconnect is a matter of education and perspective within conventional medicine.

"Most [conventional] medicine is aimed at a diagnosis," she says, "and leaky gut is not a disease, so it doesn’t really have a diagnosis, particularly." When encountering a patient with symptoms of leaky gut, she says, "You really want to start looking underneath the hood to figure out why does this person have increased intestinal permeability? Are they under a lot of stress? Are they exposed to toxic overload? Do they have some sort of dysbiosis or infection? Or do they have food sensitivity or undiagnosed celiac disease or all these other things?"

She sees resolution of many problems associated with leaky gut through dietary changes (she favors bone broths, steamed vegetables, vegetable juices, cultured foods and mucous-forming foods) and nutritional supplements (L-glutamine, colostrum, zinc carnosine and quercetin top her list). In her observation, patients have resolved issues with migraine headaches, low energy, depression and anxiety. For people with autoimmune conditions, she says, these nutritional interventions can act like a dimmer switch to bring down the intensity of an immune system flare up.