My cat circled like a shark, swatting my soaked shoes with her paw as I peeled off my jacket. Sneakers, I realized, were a bad choice for the fish market.

Though it was only 5 a.m., I had just returned home from the New Fulton Fish Market at Hunts Point in the Bronx, one of the world’s largest fish purveyors, second in size only to Tokyo’s famed Tsukiji Market. I had tagged along with executive chef Jodi Bernhard to better understand how the seafood she served in her Spanish-style restaurant traveled from the sea to the plate.

In the (very) early morning, Jodi and I met outside the 400,000-square-foot warehouse, dodging distribution trucks emblazoned with names like “Meat Without Feet” on the side. We walked through the doors and were hit with the pungent smell of a place that processes millions of pounds of fish daily. The sheer volume of seafood inside the market was staggering. Long, wide aisles were festooned with crates of cod, catfish, eel, halibut and red snapper; clams, oysters and scallops were wrapped in net bags, kept fresh on ice. As Jodi set out to place orders, I explored the aisles.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates that Americans ate an average of 14.6 pounds of fish and shellfish per person in 2014, making the United States the second largest seafood consumer behind China. Despite our standing, the USDA recommends that we should be eating even more fish. The new 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines found that nearly all Americans, regardless of age or gender, fail to eat the suggested twice-per-week seafood intake. “Shifts are needed within the protein foods group to increase seafood intake,” the guidelines say, recommending that Americans swap proteins, such as beef, poultry or eggs with seafood. My visit to the fish market sparked some questions: With so many fish exiting the ocean daily, is it even environmentally responsible to increase your seafood consumption? Which species are sustainable, and how do you know? Should you actually eat seafood at all? Here, I attempt to shine light on the largest seafood issues and offer clarity about transparency in the supply chain, ocean health and more.

Seafood traceability: A quiet revolution

We can’t talk about the seafood industry without talking about traceability, or more accurately, the lack thereof. A 2013 report by the nonprofit Oceana found that out of 1,215 seafood samples from 674 retail outlets, including grocery stores, sushi venues and restaurants across the United States, DNA testing found that one-third of seafood was marketed as a different species. The worst culprits were snapper and tuna, which were mislabeled a whopping 87 percent and 59 percent of the time, respectively.

We can’t talk about the seafood industry without talking about traceability, or more accurately, the lack thereof. A 2013 report by the nonprofit Oceana found that out of 1,215 seafood samples from 674 retail outlets, including grocery stores, sushi venues and restaurants across the United States, DNA testing found that one-third of seafood was marketed as a different species. The worst culprits were snapper and tuna, which were mislabeled a whopping 87 percent and 59 percent of the time, respectively.

Why does this matter? Because it indicates lack of traceability throughout the entire supply chain—if you don’t know what kind of seafood you’re buying, how do you know it was caught sustainably? Or that it was processed without using slave labor, as a devastating 2015 Associated Press report found in parts of Thailand’s shrimp industry, which supplied major restaurant chains and grocery outlets in the United States. Traceability is hard, however. Especially in an industry where seafood can sometimes pass through five, ten, even 30 hands before it gets to your plate.

The U.S. government recognizes such convolution. In 2014 the Obama administration directed establishment of a task force to combat illegal, unreported and unregulated seafood fraud and is now working to establish a seafood traceability program for species at risk of mislabeling (including snapper, tuna, shark, grouper and more). But altering governmental procedures can be like reversing a clunky, slow-moving train. It takes a long time.

As a result, small, nimble seafood manufacturers are rising to meet market demand for traceable, sustainable seafood. “We founded Salty Girl to provide better access to sustainable and traceable seafood,” says Norah Eddy, cofounder of Salty Girl Seafood, which packages ready-to-eat and frozen fish. “The way we started doing that was sourcing directly from fishermen, because traceability is easiest when supply chains are short, as opposed to traditional seafood supply chains that have really long and convoluted supply.” A Santa Barbara–based marine biologist, Eddy is passionate about creating strong connections between the consumer and the seafood supplier because it means accountability. “I don’t think there’s a lot of accountability in the seafood industry. So much of what we need right now is awareness, and I hope Salty Girl will be a catalyst for positive change to incentivize fishermen to harvest sustainably.”

Salty Girl and other seafood companies like Fishpeople innovate in traceability by including tracking numbers on the back of each product package; enter this number into the brand’s website and you’ll receive information like where seafood was caught, the fisherman or name of the fishing vessel and sustainability certifications. A recent batch of Fishpeople’s Wild Seafood Bouillabaisse, for example, contains pink shrimp caught off the Oregon coast by a Marine Stewardship Council (MSC)–certified fishery and docked in Ilwaco, Washington. Such granular information is wildly impressive, considering that many conventional brands provide no traceability information at all.

One thing we know for certain: People increasingly want to know where their food comes from. Over the past few years, land-based food production has excelled in providing such information. Notably, brands like bread company One Degree Organic Foods profile their grain suppliers on their website and Patagonia Provisions sources its entire line of grass-fed bison jerky from one conscious ranch, Wild Idea Buffalo. Such detail in seafood lags. But experts like Barton Seaver, director of Harvard’s Healthy and Sustainable Food Program at the Center for Health and the Global Environment and author of the cookbook Two If By Sea (Sterling Epicure, 2016), believe change will spark from manufacturer, retailer and consumer perspectives. “Traceability is going to come from across the board. Manufacturers and retailers are going to lead the conversation because they have a unique opportunity to guide government policy on this,” says Seaver. “Seafood information hasn’t followed the fish to the consumer because nobody’s asked for it. Our expectations of what supply chain systems furnish for us need to change …we need consumers to demand this.”

How greened-up aquaculture is changing the game

Farmed fish has a bad rap—and for good reason. Aquaculture—described as the “breeding, rearing and harvesting of plants and animals in all types of environments, including ponds, rivers, lakes and the ocean” or contained environments—is a decades-long practice that historically had highly negative impacts on fish health and the environment. One scary 2009 study published in the International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health found that some farmed fish had a “higher body burden of natural and man-made toxic substances,” including antibiotics and pesticides—chemicals applied to mitigate disease in densely stocked fisheries—than did wild fish. Old-school aquaculture operations also failed to properly recycle water, causing excess fish and water waste to pollute nearby waterways.

But aquaculture remains an important sector in seafood production. A report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) found that in 2012 aquaculture provided almost half of all fish for human food globally—by 2030, this share is projected to rise to 62 percent. “If responsibly developed and practiced, aquaculture can generate lasting benefits for global food security and economic growth,” says the report—a statement that sounds, well, fishy if you’ve heard that farmed seafood harms the environment.

But aquaculture remains an important sector in seafood production. A report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) found that in 2012 aquaculture provided almost half of all fish for human food globally—by 2030, this share is projected to rise to 62 percent. “If responsibly developed and practiced, aquaculture can generate lasting benefits for global food security and economic growth,” says the report—a statement that sounds, well, fishy if you’ve heard that farmed seafood harms the environment.

But over the past decade, farmed seafood not only increased output to feed a growing population, it did so responsibly. And some operations have figured out how to produce healthy fish in a highly sustainable manner. Take Australis Barramundi, for example, a fresh and frozen farmed fish company that raises barramundi in both closed-containment (land-based) tanks in Turners Falls, Massachusetts, and offshore in central Vietnam. Australis is considered the gold standard in large-scale aquaculture—the company recycles and purifies 99 percent of its water and donates fish waste as fertilizer to local farmers; in Vietnam, Australis is the only open-ocean aquaculture to receive the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch “Best Choice” rating for sustainability, arguably the most robust seafood rating guide in the United States.

Another smart choice? Farmed oysters. Often raised in coastal areas, farmed oysters don’t need external feed (they instead eat nutrient-dense phytoplankton floating in the water), nor do they require application of chemicals like antibiotics or pesticides. They can filter murky water—one oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water per day—and cultured oyster reefs even provide a natural coastal buffer that can mitigate shoreline erosion, according to a 2014 Seafood Watch report. Although Seaver typically recommends that shoppers eat small portions of seafood, he wholeheartedly encourages eating oysters and other farm-raised mollusks.

“I consider clams, mussels and oysters to be restorative. Every time you eat the oyster, you’re incentivizing oyster farmers to raise more and you’re putting more people to work in oyster farms,” he says.

Just as there are some bad poultry, beef and pork factory farms, there are bad fish farms. Not all aquaculture is good. But a growing number of seafood farms operate with ecological and social integrity—and that’s something to get excited about.

The wild card

Wild-caught fish in the United States are well managed. Thanks to stringent regulations by state fishery management agencies, overfishing concerns are minimal. “It’s important to consider that our fisheries are doing well,” affirms Eddy. “The developed world has done a pretty good job at managing [healthy fish stocks].” Part of the reason why U.S. fisheries are doing so well is because there’s economic motivation to preserve wild species of fish—it’s in each state’s best interest to encourage fishermen to employ sustainable fishing practices, with methods such as pole-and-line and trolling.

Alaska has one of the best-controlled wild-fish stocks—especially salmon. Biologists use sonar technology to assess salmon populations, and “a limited number of licensed fishermen using regulated gear are allowed to fish in state waters up to three nautical miles offshore for restricted periods of time,” writes Diane Morgan, author of Salmon: Everything You Need to Know + 45 Recipes (Chronicle, 2016). As a result, wild-caught Alaskan salmon are considered a sterling seafood option.

Alaska has one of the best-controlled wild-fish stocks—especially salmon. Biologists use sonar technology to assess salmon populations, and “a limited number of licensed fishermen using regulated gear are allowed to fish in state waters up to three nautical miles offshore for restricted periods of time,” writes Diane Morgan, author of Salmon: Everything You Need to Know + 45 Recipes (Chronicle, 2016). As a result, wild-caught Alaskan salmon are considered a sterling seafood option.

When buying wild-caught fish, both Seaver and Eddy recommend buying domestic species. Not only because it supports American fishermen and boosts local economies, but also because developing nations still lag behind in fishing regulations. “About 50 percent of our global catch is harvested from fragmented fisheries in developing nations. How do we bring these fisheries up to par?” asks Eddy, who says some of these fisheries lack infrastructure to handle fish from a quality, traceability or social standpoint (example: Thailand’s slavery allegations in shrimp processing). If domestic fish stocks are an industry bright point, poorly managed wild-catch operations overseas still need work.

What now?

Sustainability is complicated. And because there’s ample variation in how fish is caught and raised, buying it can be an arduous task. It’s hard to remember that whitefish from Lake Michigan, Wisconsin, is good but whitefish from Lake Superior, Wisconsin, is bad. But overall expert consensus agrees with the Dietary Guidelines: Yes, eat more seafood. But be picky.

Morgan recommends befriending your fishmonger, the person in your grocery or natural retail store who receives and orders seafood. Ask where it came from; ask when it was caught. Also download the Seafood Watch app (it’s free!) to search for the best fish options when you’re at the store (you can also download and print out a guide from seafoodwatch.org).

Seek out manufacturers of packaged seafood products that don’t just tout their traceability commitment but also prove it via information on their website or back-of-package tracking information. Don’t know where the fish in your favorite canned tuna came from? Call the company and ask. Your inquiry will show mainstream food manufacturers that shoppers care about catch location.

But perhaps Seaver’s recommendation is the easiest (and tastiest) to follow: Diversify your protein choices by eating chicken, beef, tofu, nuts, legumes and seafood—and choose smaller portions. Prioritize eating small fish and shellfish such as anchovies, sardines, clams, mussels and oysters. If you do buy larger, predatory fish like tuna, make it count: Buy the freshest and best 16-ounce piece of tuna you can buy, cut it into four pieces, and cook it with care. Invite over three friends, open a bottle of Burgundy wine, and serve the fish with a lot of vegetables. Savor, and repeat twice per year. Doing so will respect the integrity of the fish and inspire you, your friends and your community to cherish fish—and the people who caught it—as an important resource, Seaver says. “This is the only chance we have to honor the role food producers play in our food system.”

Super seafood picks

Australis All Natural Barramundi Frozen Fillets. Each pouch contains two fillets of sustainably farmed barramundi, flash-frozen within hours of harvest and vacuum-sealed for freshness.

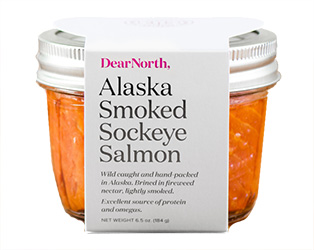

DearNorth Alaska Smoked Sockeye Salmon. This minimally processed sockeye is smoked with alder wood and mixed with a light brine, containing sea salt, brown sugar, fireweed blossoms and lemon zest.

Fishpeople Wild Crab Mac’ and Cheese. A classic comfort food made with deep-sea red crab, caught in an MSC-certified fishery off the mid-Atlantic coast.

SafeCatch Elite Wild Tuna. SafeCatch tests every single tuna for mercury to prevent contamination and works to clean up factory waste streams that caused mercury pollution in the first place.

Salty Girl Seafood [Smoked] Albacore Tuna. A fully traceable, ready-to-eat tuna caught from the Pacific Northwest with pole and troll methods.