Real Food Farm

Real Food Farm

How can healthy food become accessible to all? An in-depth look at America's changing food landscape @deliciousliving

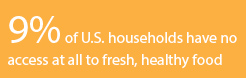

It’s been a long time coming, but in many areas of the country, healthy food is getting easier to find. Stores from 7-Eleven to Walmart now carry organic products, helping to drive prices down and convenience up. But a deeper look at the nation’s food landscape reveals a stubborn inequity: According to the USDA, roughly 9 percent of U.S. households still have no access at all to fresh, healthy food. And for countless others, even if it’s on nearby shelves, it’s financially out of reach.

“It is still not uncommon for people in some areas to say to their neighbor: ‘What gas station do you get your groceries from?’” says Fred Haberman, cofounder of Urban Organics, which uses aquatic farming to bring certified-organic vegetables to underserved urban areas. Adds Josh Tetrick, founder of food technology company Hampton Creek: “We live in a time where the unhealthy choice is dirt cheap and convenient and the healthy choice is pricey and inconvenient.”

Decades-old problem

Experts trace the accessibility problem to the 1960s and ’70s, when white, middle-class families fled cities for suburbs, bringing supermarket chains and independent natural grocers along with them, says Allison Hagey, associate director at Oakland, California–based nonprofit PolicyLink. For people who stayed behind, few if any groceries remained within walking distance. Rural areas with faltering economies experienced similar depletion, and for many rural dwellers without cars, accessing healthy food became a significant chore. “We hear of people traveling an hour or two on multiple buses just to get groceries,” says Hagey, also a member of PolicyLink’s Food Access Team. Meanwhile, fast-food restaurants, convenience stores, and other sources of cheap, processed food opportunistically moved in.

Today, according to the USDA, nearly 24 million people live in so-called “food deserts” with no easy access to healthy food. A new PolicyLink report shows that low-income, urban neighborhoods with high minority populations have the least availability while—not surprisingly—white, college-educated, high-income neighborhoods have the greatest. One study of 22 Native American reservations in Washington state found that 15 had no grocery store at all.

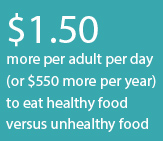

Regardless of location, many people feel priced out of healthy offerings—and for good reason. One 2013 study published in the British Medical Journal found that it costs $1.50 more per adult per day (or $550 more per year) on average to eat healthy food, such as fresh fruits, vegetables, and meats, versus unhealthy food. Researchers noted that this is a “trivial” price to pay to avoid chronic diseases but acknowledged that, for disadvantaged populations, cost is a “key impediment” to eating healthy. “Lowering the price of healthy diet patterns should be a goal of public health policy,” the authors concluded.

The role of retailers

Grocery stores, farmers’ markets, and other healthy food retailers are key players in the quest to bring healthy food to underserved areas, says Hagey. But leases can be tricky in buildings with multiple owners. Added security may be required. And with limited money, small players can have a tough time getting started or remaining open.

To offset extra costs, PolicyLink and other agencies got together in 2009 to lobby for the federal Healthy Food Financing Initiative (HFFI). Since 2011, HFFI has distributed more than $109 million in grants to help fund 100 projects, from new stores to co-ops to urban farms. The recent Farm Bill authorized the HFFI for another $125 million over the next five years. Among its recipients: Mariposa Food Co-op in West Philadelphia, which used its funds to quintuple its space, boost its local and organic offerings, and create ten new jobs; and Bottino’s ShopRite, a family-owned grocery based in Vineland, New Jersey, which used the money—along with other grants and tax credits—to open a state-of-the-art supermarket in a blighted food desert.

Improved access also means making local food easier to get, says John Fisk, director of the Wallace Center at Winrock International, a nonprofit that works toward more sustainable food systems. Food hubs, for example, gather fresh farm products from relatively small producers to a central location, which then manages, markets, and distributes the food to stores, taking those cumbersome tasks out of the hands of busy farmers. The retailer wins because just one truck pulls up loaded with local products; shoppers win by getting more fresh food at lower prices. “It’s a shorter supply chain with fewer people involved who need to get their piece of the action,” says Fisk.

Urban farms and mobile markets also offer solutions. In 2009, a coalition of Baltimore-area volunteer groups, nonprofits, and government agencies transformed an unused dirt patch in northeast Baltimore into Real Food Farm. Today, 8 thriving acres on three sites provide fresh produce to surrounding food deserts via farmers’ markets, CSAs, and collaborations with farm-to-table restaurants. Three times a week, a refurbished Washington Post delivery van heads out to neighborhood gathering places to deliver discounted fresh produce and educate residents on how to prepare it. Last year, the mobile market tripled its sales.

“Having the farm here and having the mobile market decreases the amount of energy required [for people] to go out and find healthy food,” says Shelley White, program coordinator for Real Food Farm. “It is one small solution to the grand problem.”

Year-round access to fresh food

This year, the fledgling Urban Organics took over a 55,000-square-foot red-brick warehouse in the food desert of East St. Paul, Minnesota, and transformed the interior into a sea of glistening, blue pools filled with tilapia. Nearby on stacked trays, organic kale, Swiss chard, Italian parsley, and cilantro flourish. In this cutting-edge closed-loop system, known as aquaponics, the fish provide the nutrients that the plants need, and the plants act as a filter to improve the water quality. Once harvested, the fish and vegetables appear on local store shelves within a day or two. Ultimately, Haberman believes aquaponics could provide “hyperlocal” year-round access to fresh food. “This is a test for a movement that can be scaled nationally,” he says.

With help from heavy-hitting investors, food-technology company Hampton Creek recently launched a plant-based mayonnaise with faux eggs, billing it as more humane, healthy, and sustainable—and considerably cheaper—than the real thing. Four flavors of Just Mayo now sell nationally in numerous natural and mainstream stores, including Whole Foods, Kroger, and Costco.

Tetrick made a conscious decision not to strive for USDA Organic certification for Hampton Creek products (they are Non-GMO Project Verified) because that costly process would boost the end price, defeating his purpose. As he puts it: “Solving a problem means actually solving a problem for most people—not just the folks who can afford to pay $5.99 for organic eggs.”

Architects of HFFI and Real Food Farm also steered clear of the “O” word when setting standards for what healthy means. “A lot of people don’t necessarily look for the label ‘organic,’” says White, noting that Real Food Farm is not certified but “uses organic practices.”

“People just want to know how it’s grown.”